An entire phishing simulation industry has emerged to combat the dangers of phishing attacks on individuals and organizations. To an engineer, the approach makes sense: People click on links. Let's send people practice emails and see if they click. If they click, let's give them additional training, so that they will not click again.

Phishing simulation service providers present data that suggests their approach is effective, but the scientific community is far from agreeing. Many studies on simulated phishing effectiveness suffer from small sample sizes and/or a lack of diversity among the participants.

So the science is still very much out. A recent study* suggests employees that receive phishing training may actually be more prone to dangerous actions when they receive phishing emails. Wait, what?

Direct negative impact of phishing simulation training

This large-scale study by the Department of Computer Science ETH Zurich in Switzerland* sought to measure the effectiveness of phishing simulation exercises, as well as the effectiveness of combining phishing simulations with contextual training. Contextual training refers to a common practice of forwarding participants that clicked or took dangerous actions to training pages immediately after their mistake.

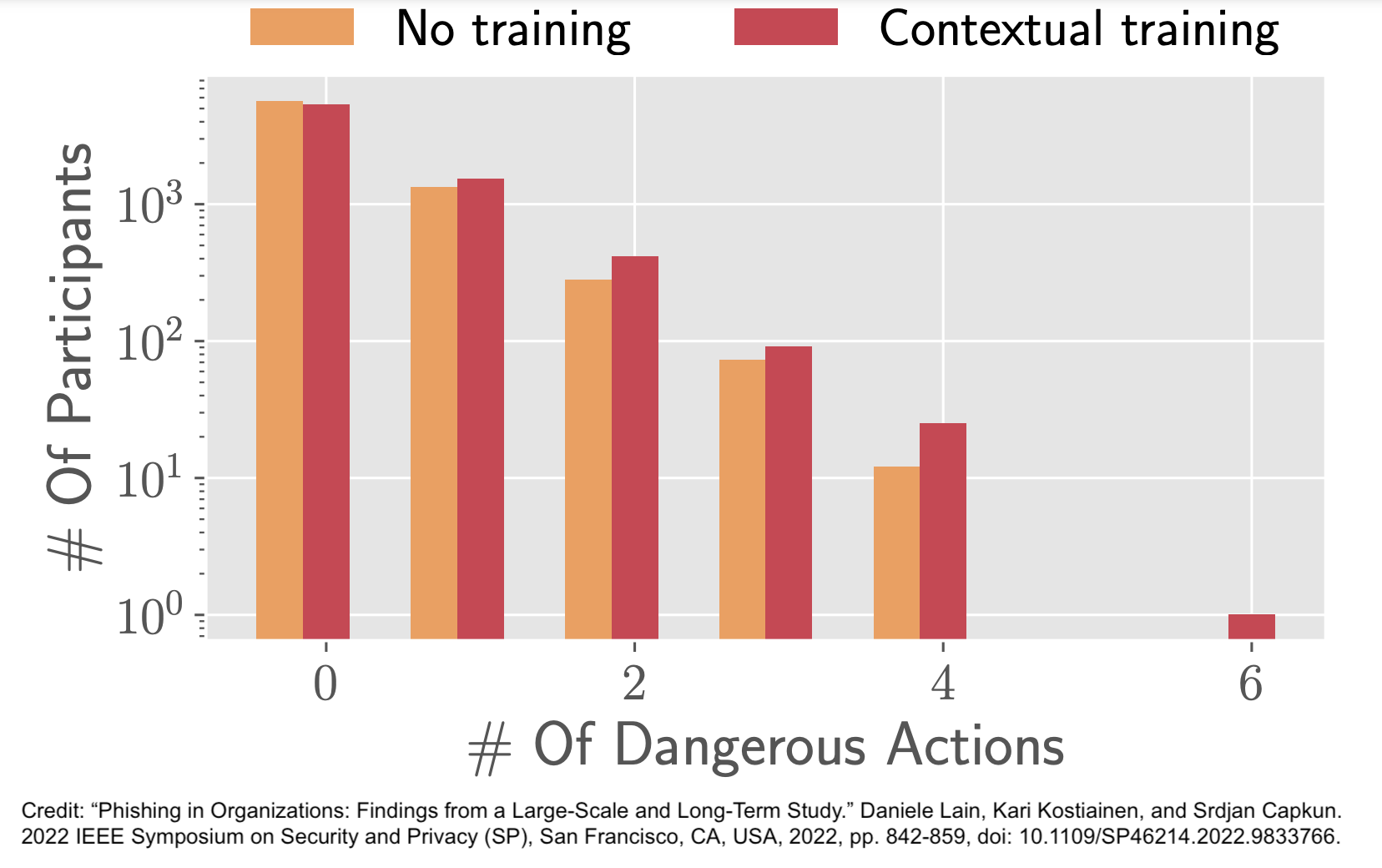

The study found that both click (+16%) and dangerous actions rates were higher (+27%) for participants that received contextual training after falling for simulated phishes. How is that possible? The researchers tried to dig deeper with a survey. Based on the survey results, they suspected that employees who were directed to training pages may have experienced a false sense of security. They may have felt more confident in their employers being able to protect them, so no need to be too cautious. They may have also felt that incoming phishes were likely just tests, so no risk in clicking.

It is also worth noting that they conducted this study at an organization that employs "people with different duties: field workers, branch workers that work in front-end stores in contact with the general public, and office workers of different qualifications, from IT to marketing and accounting." Results may have been different, for instance, in an IT or tech company with primarily highly technically skilled employees. It is also possible that the contextual training just was not that good.

We need more science to understand why contextual training did more harm than good, and what we can do to make training more effective.

Indirect negative impact of phishing simulation training

Because phishing simulations make sense and can at least seem effective, we hardly talk about their indirect negative impact. Yet, various studies suggest that simulated phishing campaigns hurt both employees’ trust in their own abilities (self-efficacy) and their trust in the organization. Both easily negatively affect other organizational goals. Both are easily understandable results of your own organization tricking you, and you falling for it.

What choice do we have?

Phishing remains a big problem that technical controls still cannot mitigate adequately. Employee skills are essential. The cited study suggests improving employee reporting of phishing incidents by increasing transparency and making reporting more rewarding for employees. This is a low-cost way of improving an organization's resilience to phishing attacks. Rewarding crowd-sourcing of phishing detection also has positive effects on:

- Employee's trust in the organization. When the security team informs about how they managed the incident after the employee reported it, it further encourages reporting and strengthens trust in how the organization operates.

- Employee's self-efficacy. Through rewarding and learning about the impact of your action, you gain confidence in your own abilities and learn that your organization valued your effort.

It is also possible to provide hands-on phishing education that does not damage employee's self-efficacy and trust in the organization. The key there too is transparency. We should never administer phishing simulations without prior warning, and at least optional pre-test training. We should also take care to ensure training materials and messaging are inclusive.

Phishing simulation training has become the status quo of security training. If phishing training is ineffective or doing more harm than good, what will it take for us as an industry to move on?

*D. Lain, K. Kostiainen and S. Čapkun, "Phishing in Organizations: Findings from a Large-Scale and Long-Term Study," 2022 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Francisco, CA, USA, 2022, pp. 842-859, doi: 10.1109/SP46214.2022.9833766.